Promoção de luta livre

A luta livre profissional evoluiu para uma exibição atlética a partir de competições legítimas por dois motivos. Escrevi extensivamente sobre a primeira razão. As disputas legítimas entre lutadores igualmente habilidosos costumavam ser longas, assuntos chatos com pouca ação. Essas competições afastaram os fãs e impediram que a luta livre profissional explodisse como um esporte para espectadores..

Não escrevi muito sobre o segundo motivo. The emergence of powerful promoters in large cities or areas in the United States in the late 1910s and early 1920s. Once political connected business owners took over the sport, the business owners wanted to control all aspects of the sport including the wrestler who carried the world championship.

Photo of Jack Curley from 1910 (Domínio Público)

During the first couple decades of the sport, local sporting men often served as promoters by securing a venue for a match that they wanted to see. These backers often took a bath on the event because crowds numbered in the hundreds. The spectators did not generate enough revenue to pay the wrestlers or cover the rent for the venue.

The Edwin Bibby vs. Joe Acton match in 1882 is an example of this promotional arrangement. Local New York sporting men put up the money to rent Madison Square Garden. Bibby defended the American Heavyweight Wrestling Championship in front of three hundred spectators. The paying crowd did not come close to paying for the venue much less reimbursing the sporting men for the $350 winner’s purse. The backers took a large financial loss.

Entre 1890 and 1910s, the wrestler’s manager also served as a quasi-promoter in lining up backers and venues for big matches. Em 1910, Frank Goth’s manager, Emil Klank, arranged with Chicago’s Empire Club for the club to secure a venue for Gotch’s title defense with Stanislaus Zbyszko.

Gotch demanded sixty percent of the gate receipts. The Empire Club took thirty-five percent leaving Zbyszko with only five percent of the gate.

In the early 1910s, local business men began opening promotions in the larger cities and towns. Jerry M. Walls may be the first regular promoter of a town. He managed Ed “Strangler” Lewis during Lewis’ time in Kentucky. Walls gave Lewis his name as Lewis previously wrestled under his real name, Robert Friedrich, or Fredrick.

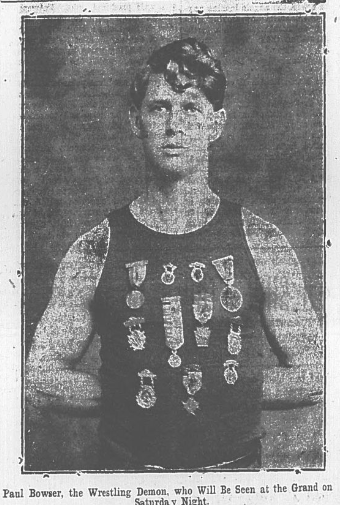

Photo of Paul Bowser as a wrestler in 1914. He promoted professional wrestling in Boston for several decades. (Domínio Público)

Walls promoted Lexington, Kentucky, his hometown and Louisville, Kentucky, between 1913 e 1915. Lewis regularly main evented these cards.

When Lewis left for New York with a new manager, Billy Sandow, Walls quit promoting both wrestling and boxing. I cannot find any reference to him after 1915.

Jack Curley set himself up as the first big city promoter, when Curley opened his promotion in New York City during 1915. Curley partnered with Sam Rachmann on Rachmann’s fall version of the 1915 New York International Wrestling Tournament.

Originalmente, Curley promoted boxing and wrestling. Tex Rickard squeezed Curley out of boxing, so Curley focused on professional wrestling. Using his political connections and control of the biggest potential market in the country, Curley soon controlled the world championship.

By the early 1920s, Paul Bowser set up his promotion in Boston. Tom Packs controlled St. Louis. Other regional promoters opened promotions in large to mid-size cities throughout the United States and Canada. These promoters wanted to control everything in professional wrestling, so they effectively ended legitimate contests. The only legitimate contests after local promotions appeared were double-crosses or agreed upon contests to settle promotional differences. Legitimate professional wrestling ended in America.

You can leave a comment or ask a question about this or any post on my Facebook page.

Sources: The New York Times, Agosto 8, 1882, p. 2, Star Tribune (Minneapolis, Minnesota), Fevereiro 15, 1910, p. 10 e The Lexington Herald, Julho 1, 1913, p. 9