Changing Tastes

In November 1923, St. Louis Star-Times reporter Billy Murphy interviewed St. Louis wrestling promoter John Contos. Murphy proposed to Contos that the era of dominant wrestlers like William Muldoon was over. Murphy spoke about the recent match between “World Champion” Hardneck Phillips and the game contender Webster O’Malley.

Phillips successfully defended his championship by throwing O’Malley after 1 hour, 50 minutes. The likely “worked” match left both men utterly exhausted.

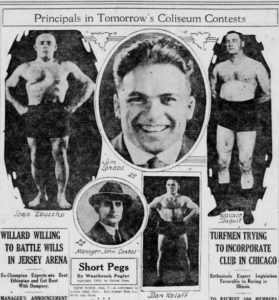

Newspaper article about John Contos’ St. Louis Wrestling Card in 1923 (Public Domain)

My doubts about the validity of the match were raised because Contos defended the longer bouts claiming the wrestling audience wanted to see longer matches. Contos stated that fans wanted to see a variety of holds and predicaments over longer matches. Contos argued that a match lasting only one or two minutes would be considered boring.

Contos must have raised eye brows with his comparison of professional wrestling to the Ziegfield Follies and other stage shows. Although he claimed fans wanted “honest contests”, he frequently compared wrestling to stage shows. Contos chose an odd analogy considering that accusations of fixed matches had been made since the 1800s. Several journalists referred to the wrestlers as acting mastodons, so it is odd for someone in professional wrestling to be making this same comparison. Contos’ comments also illustrate how tastes change throughout the years.

Professional wrestling evolved into primarily, if not exclusively, “worked” (prearranged) exhibitions for three primary reasons. The first was legitimate bouts carried a greater chance of injury, so wrestlers began working with each other to put on good matches without hurting each other. The cooperating wrestlers would split the payoff between the two of them instead of winner take all.

Second, promoters gained control over championships, and access to bigger live gates by having the championship defended, by controlling the outcome of matches. “Double crosses” occurred when a promoter sent one of his “shooters” to take a championship despite previous agreements with other promoters. He risked the other promoter’s ire because controlling the championship could be lucrative for his own wrestling cards and by lending out the champion to other promoters.

One of the less talked about reasons but the focus of this article is that “shoot” or legitimate wrestling matches could be both long and boring. William Muldoon, who threw a number of wrestlers in minutes as Murphy pointed out in the beginning of his article, wrestled a seven hour draw with Clarence Whistler. I wonder how many fans were there at the end of that match?

Ed “Strangler” Lewis and Joe Stecher wrestled several two-hour draws that were said to be “shoot” matches. The biggest problem with a “shoot” was two equally matched wrestlers like Lewis and Stecher could tie up for hours looking for a take down or hold. Wrestlers stuck together in collar and elbow tie up for hours looking for a hold can be as exciting as watching cars rust.

Joseph “Toots” Mondt, Lewis’ partner and a promotional genius, started adding in concepts such as good guys and bad guys and shorter matches with multiple falls in an hour to make wrestling more exciting.

By the 1930s, wrestling matches rarely went over an hour. When these matches did go longer, it was normally the conclusion of a feud and would be the last match on the card between the two biggest stars.

Despite Contos belief that shorter matches wouldn’t be very entertaining, the 1980s introduced much shorter matches including 2 to 3 minute matches even between well-regarded wrestlers. If you watch one of the 20-minute acrobatic performances of today, which passes for professional wrestling, you will quickly see why shorter matches are needed at times.

In the next few years, matches may get shorter for a while but the trend may go back to longer matches. Over time, trends go back and forth as wrestlers adapt to their audiences. 17,000 fans came out to see Phillips defeat O’Malley, so Contos must have known his audience at the time.

You can leave a comment or ask a question about this or any post on my Facebook page.

Source: St. Louis Star-Times, November 5, 1923 edition, p. 15

Pin It